“Slay the monolith!”

Workshop Summary: “Designing Microservices with Sam Newman”. Some Thoughts about the Why, What and How when it comes to Microservices

Intro

The term microservice can be understood as a powerful approach to develop resilient, scalable and flexible applications - and at the same time it is the most hyped buzzword during the last years in the software industry. We had the chance to meet one of the famous names around microservices: We met Sam Newman at a workshop about

designing microservices at the QCon London. He is the author of the book „Building Microservices“, independent consultant and speaker based in London (https://samnewman.io/).

Sam Newman: Building Microservices.

This post sums up some of our learnings and thoughts from this workshop. For you as reader it means, you will get some snapshots from an architectural two days workshop, short statements where you can agree or disagree, according to your own experience, and some further tools, literature and links.

Get a common understanding about WHAT are Microservices

Let’s first talk about the definition of microservices: According to Sam, “microservices are a style of SOA”. At Netflix, this type of architecture was called “finegrained SOA” before the term microservices was branded. Microservices consist of autonomously deployable artifacts and are built around well defined business contexts.

As the term micro implies, the services should be small scoped. But rather than measuring a service size by its lines of code or similar metrics, it should be measured by number of concerns: it should have only one! Having one service per concern leads to a large number of services when creating or splitting up a medium sized application. Those services need to be operated and coordinated, which brings new complexity to the system and team.

Compared to a monolithic world, distributed systems come with multiple obstacles and challenges along the way. Deployment, monitoring, logging, trouble shooting, distributed configuration and handling of consistency and transactions are getting more complex. Even though there are best practices and tools which address each of these topics, these tools need to be understood and mastered by the team. In addition the business has to understand the main points of microservices as well, simply because the services should be defined around business contexts.

On the other hand, when done right, microservices have a lot to offer:

- dynamically scalable applications,

- autonomous and independent teams,

- shorter time to market,

- free to choose best-fit technology per service without affecting other services,

- less code per context,

- build more resilient systems.

Clarify WHY you like to do it

If you think about doing microservices, the central question you should ask yourself is: Why? Why do you think, microservices would help in your context? Are there other options or less complex approaches to achieve that goal? A common main driver from the business point of view is reducing the time to market. But that goal could also be achieved by other means, like automation within the existing structure.

Also think about your organisation, if the costs of getting something done is high, it could be also related to bad organisational environment and not to technology.

Microservices are no silver bullet and you can build successful products using traditional approaches. Sam named salesforce as prominent example of a large and successful (fifteen-year-old) monolith. Etsy and facebook started using an traditional approach, as well.

Or, like Michael Nygard states in the recently published second edition of his basic work about how to design resilient and production ready software, Release it!, “don’t pursue microservices just because the Silicon Valley unicorns are doing it. Make sure they address a real problem you’re likely suffer. Otherwise, the operational overhead and debugging difficulty of microservices will outweigh your benefits.”

Michael Nygard: Release it! Second edition.

Microservices unleash their full potential when they are backed by your organization’s structure. They fit perfectly when you have - or aim at having - autonomous, self-reliant teams. Those teams can work independently, choosing their own speed and technology. They “own” their service, meaning besides building it, they also maintain and operate it. Instead of micromanaging those teams, give them a clear goal and leave it up to them, how to reach it within short iterations and feedback cycles.

On the other hand, if your organizational structure does not fit and is not willing to adapt, you should think twice about whether microservices are the right choice in your setting.

Therefore first clarify within your company or team what are the business needs and the strategic goals within your context. Check if microservices support their achievement and which architectural principals and design patterns within the microservice approach support your goals.

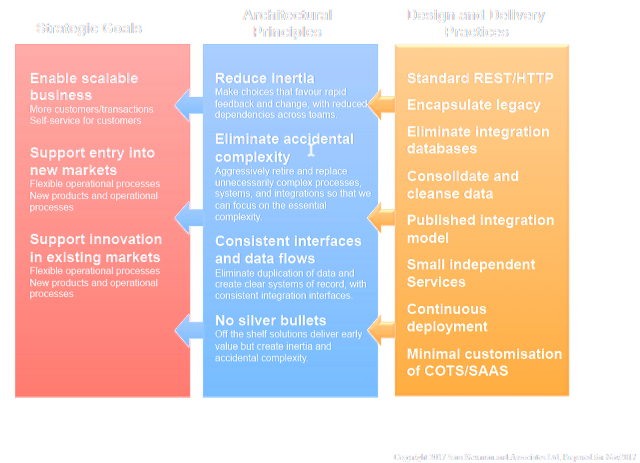

Common strategic goals in the software industry are e.g. enabling scalable business, supporting entry into new markets or speed up innovation cycles within existing markets. The chart below shows these strategic goals, their derived matching architectural principals and the underlying design patterns.

Plan HOW you start your transition

General hints

If you have defined your strategic goal - e.g. more team autonomy, higher scalable application or use of new technology - and start with the implementation, Sam recommends to set periodic checkpoints. At these checkpoints review what you have done and if your actions are supporting your goals so far. Where possible, your reflection should be based on measurable data. And you should also ask your customers for feedback. Be open and decide what needs to be changed before going further. About the frequency of these checkpoints it can be hold once a week for a single team and additional overall reviews with less frequency for multiple teams.

Further general advice from Sam: Do as less upfront design as possible and start with small continuous steps.

Sam warns, not to change your technology stack during the first run but first try to get familiar with the underlying concept itself. If you just switch the technology and add several tools to your stack, there is the risk, that you concentrate more on the technology then understanding basic concepts within your team. First frame the problem, then search for the pattern which solve the problem, at least search for technology which supports these patterns.

To get used with the complexity it is good to start with a small number of services. Those should be brought into production quickly, in order to get fast feedback from within a productive environment. Get heavy load on these services and then go forward by splitting these services, where needed from the evidence of lessons learned from production.

The process of migrating to microservices is more like a slider than a switch. It is a constant journey. Therefore you should set your goal upfront, to find the supported patterns for a proper solution … and still it will be a long journey with back and forth.

Observability

Having distributed components makes it more difficult to understand and monitor how the application as a whole behaves and how the components interact with each other. It is very important to take this into consideration up front.

One must-have, for instance, is setting up a proper log aggregation (see e.g. ELK-Stack). That allows you to collect and aggregate application logs from all components in a single place in order to spot how those components affect each other. It also allows you to get structured access to your logs and thus derive common metrics and visualizations from your logs.

Beside that practical aspect, setting up log aggregation is a good test for yourself, since, as Sam stated, “if you can’t get log aggregation up and running - microservices is not for you”.

Whereas log aggregation is the first step to make your application observable, you can - and should - go further than that. And doing it upfront is much easier than trying to add it when you face your first non trackable phenomena in production.

A common way is instrumenting your application by exposing monitoring endpoints, which allow to collect all kinds of metrics from within your application. Those can be used to create monitoring dashboards and set up an automated alerting when those metrics start to go south (see e.g. Prometheus, Grafana).

When your application is split into multiple services it may be difficult to track how interrelated calls make their way through the system. A way to address that is adding tracing capabilities to the services (see e.g. OpenTracing, Jaeger, hands-on tutorial).

Even if those tools help you to get deep insight into how your application works, you still may want to attach an interactive debugger to hunt down specific behaviour. Squash tries to give you the same debugging capabilities you are used to from a non-distributed application (set breakpoints across services, modify values, …).

(Re)design and service boundaries

Having that said, it is time to actually have a look at how you can split your application into distinct services.

Sam recommends an iterative approach, since, quoting Martin Fowler, “the only thing a big bang rewrite guarantees is a big bang!”. Start by identifying one part of the application, which would be a good candidate to extract as a distinct service. There are different approaches for that.

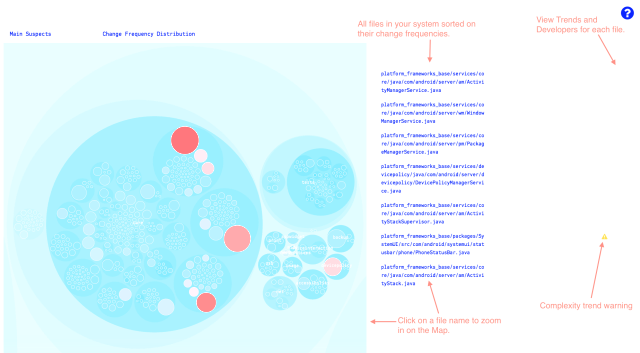

For example, if you aim at shorten your time to market, one start point could be to look at the code liveliness and extract a part of the application, which has a high rate of change. The static code analysis tool codescene supports this by generating hotspots according to the frequency of changes.

A general advice when splitting up an application is “what changes together stays together”. That helps to prevent ending up with services having lots of dependencies to each other.

A different approach doesn’t focus on your existing application but on your product backlog. Check whether it contains use cases, which can be implemented in a self-contained service. So you won’t have to deal with legacy code and instead try to quickly bring that new feature to market.

If the main driver for starting with microservices lies in scaling, Sam recommends to first identify the bottlenecks in your application by doing automated performance tests. Gatling or FlameGraph can help you to find bottlenecks. Those can be candidates to extract as separate services.

A general pattern for migrating an existing monolithic application into a microservice architecture is the Strangler Pattern. It suggests to build the structure upon the old one, gradually consuming and finally replacing it (see Paul Hammant: Legacy application-strangulation-case-studies, Strangler Application by Martin Fowler) .

If you start with a greenfield project, it is most important to identify logical boundaries within the application to build. That can be done by grouping coherent/cohesive features into reasonably small groups (remember: one concern). Sam calls these groups capabilities.

That’s basically what Domain Driven Design deals with. Finding bounded contexts within the application which can be considered independent to each other (see e.g. Martin Fowler on bounded contexts).

Vaughn Vernon: Implementing Domain Driven Design.

Vaughn Vernon: Domain Driven Design Distilled.

There are several methods for doing that. A recent one is called event storming, which suggests to collect events (user actions like ‘add item to cart’) on post-its.

Those post-its are easy to group and - even more important - easy to iteratively regroup when you notice the first flaws creeping into your model.

Alberto Brandolini: Event Storming.

That may sound easier than it is. We did a practical exercise in the workshop, where we modelled such capabilities for an eCommerce/retailer use case in small groups (4-5 people). Even though the use case was quite assessable and clear, the results of the groups differed in some aspects. The collaborative character of that method is a good way to get all involved stakeholders (both, from business and tech) at one table and start to get a common understanding of the application’s capabilities, service boundaries and a possible MVP worth to start with.

Picture taken at the workshop, where we modelled an application according to its capabilities.

Designing your application and service boundaries on the clipboard still may uncover some surprises as soon as the plan hits reality. Redesigning your model once the first services are built is more difficult that redesigning it within a single code base. That is why not few people, including Sam and Martin Fowler, recommend to think about starting with a monolith and extract services as soon as the model consolidated within the running application.

Testing

Using microservices also affects the way you test your application.

Whereas it might seem easier to test a service within its defined borders, it for sure gets more complicated to test the interplay of different services.

Mountbank jumps in by mocking remote services, so that you can test your service independently of other services.

Allowing different services to be developed independently of each other also means that a service needs to rely on interfaces offered by those other services, though. Those contracts need to be stable. A way to enforce this is by Consumer-Driven Contract-Testing. This allows you to automatically test the stability of your API. Those can be implemented using e.g. Pact (multi language) or Spring Cloud Contract (Java).

Following the traditional test pyramid, end-to-end tests should be well dosed, since they are slow and expensive compared to unit- and integration tests. This seems even more true when having a microservice architecture. Having done it right, your services should be highly observable and your build- and deployment infrastructure should empower you to quickly redeploy services. Having that in place, canary releases could be more efficient than doing extensive e2e-tests (see e.g. Just Say No to More End-to-End Tests, Emily Bache’s talk about End-to-end automated testing in a microservices architecture or the recent Testing Microservices, the sane way).

Even though originating back to a time, where microservices did not yet exist (2008), Lisa Crispins book about testing in an agile environment still contains many valuable thoughts also valid in a microservice context.

Lisa Crispin, Janet Gregory: Agile Testing.

User Interfaces (UI), Micro Frontends and Backend for Frontend Services

If we talk about microservices we talk mostly about how to split a monolithic backend into multiple services. If we do it like this, don’t we talk just about 50% of our application structure, as long as we don’t touch the UI? Don’t we have the same problems on UI side with monolithic code and single deployable artifacts? To get to 100% microservices lets sketch how to split the UI.

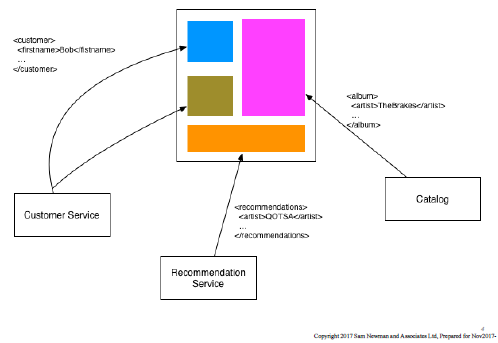

Having a single-page app (SPA), one could divide the page into different contexts, each getting its specific data from a dedicated service.

Tom Söderlund describes how this can even be done using different frontend frameworks/technologies for each context within one single SPA. He calls this approach micro frontends and it gets applied by companies like Spotify or Zalando.

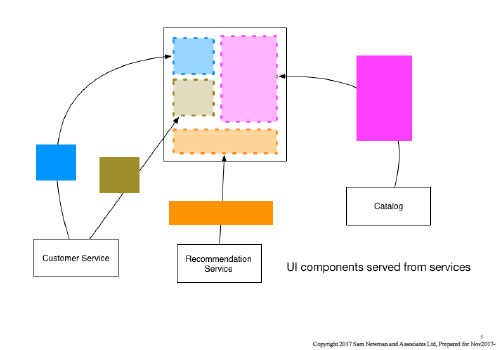

To go further and physically split the SPA, each backend service could contain its UI files itself. Those can be served as widgets and arranged within a composite UI.

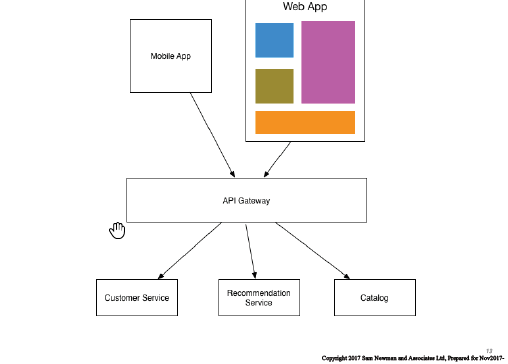

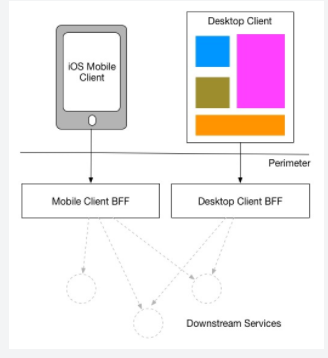

Nowadays it is important to not concentrate on web only, but also have other devices in mind. Thus, following a multi channel approach. Mobile devices bring some additional challenges: Data is slower and more expensive. And due to the reduced display size, only a subset of the data can be shown at once. One way to handle this could be to add a “aggregating gateway” between the backend and UI services. This gateway can strip out and aggregate data in order to reduce the size of the payload and the number of calls.

The downside of this approach is that the gateway could become a bottleneck by being a middleware with multi responsibilities and dependencies on code changes and deployments. Since it would need to know how to assemble the data for each use case, the clear separation by business context would be gone.

As an alternative, Sam introduced the option that each service gets a distinct backend layer, which does the corresponding data conversion for the device it is meant for. He thus calls it “backend for frontend” (BFF). Whereas the BFF is tightly coupled to a single UI, the service itself remains independent of the various UIs. The BFF is owned by the same team as the UI, so that it can adjust it as needed.

Closing Note

We could go on with further chapters about deployment, communication, security, organisation etc., but we hope you already got some useful hints for your project. Our goal was to share some of the main points from the workshop to inspire you to think further. If you are considering doing microservices, first identify your current problems and challenges, define your goals and check if and where microservices can help to solve them. Review your transition by checkpoints and start in small steps, but improve continuously.

We like to close this article with one of Sam’s first sentences at the workshop: “If you all decide after the workshop to not do microservices, I’m totally fine with it” ;)