You start a new project. In the beginning, it’s mostly prototyping; you try out ideas and nothing is fixed yet, so you are very pragmatic when it comes to the configuration of your application. Some property files are stored next to the source code - at least you are not using hard-coded URLs and credentials! When you first deploy the application to a dev or demo environment, you simply copy and modify the property files. The prototype turns into production code, yet the configuration is still managed in an ad-hoc manner. Does this sound familiar to you? It was, at any rate, the situation I found myself in with one my of current projects somewhat more than a year ago.

Maintaining separate copies of the configuration files in different environments was probably never the best approach, even when we used to deploy onto few long running snowflake servers. Given that we more and more learn to take advantage of cloud offerings, therefore often create short-lived application environments for, e.g., tests, and deploy even our production systems as phoenix servers, we need to do better.

This post describes how we approached this issue in one of our Spring Boot-based projects using Spring Cloud Config and Spring Cloud Vault and how we customized these libraries to meet our needs. In particular, the post looks at the motivation for externalized configuration and gives a (very) high-level overview over Spring Cloud Vault, Hashicorp Vault, and Spring Cloud Vault before it describes (a) the extensions we implemented to make a Spring Cloud Config client fetch the necessary HTTP basic authentication credentials from Vault and (b) how we made our applications read all TLS (client or server) key material from Vault. You can find the relevant code on GitHub in the public demo projects demo-authorized-spring-config-server and demo-spring-boot-tls-material-from-vault, respectively.

Externalized Configuration

Of course, the configuration challenge is not new, so there are tested concepts we can look at. For instance, the twelve-factor app’s tenet is that applications are to be configured exclusively via the environment: Environment variables are supported by almost every operating system and deployment model, they are easily accessible no matter which language or framework you use, and you can define them without any modifications to your deployment artifacts.

While I accept the sentiment of the twelve-factor app approach and agree with the claim that a deployment to a new environment - possibly on a different platform - is not supposed to require any modifications to the deployment artifacts, I am not convinced by a conclusion drawn by the twelve-factor app: That configurations should not be grouped together.

The reason is simple: Strictly following the twelve-factor app guideline might indeed guarantee that you can always change any configuration aspect of an application. But it merely puts the burden of the configuration management onto the deployer, it does not help to solve this challenge. In my experience, it will also cause developers to expose only the few parameters they expect to change from one environment to another; all other configurations will end up baked into the deployment artifact.

And last but not least, passing sensitive secrets via the environment does not sit well with me: It might be ok if you can guarantee that the VM the application runs on is not shared at all - in this situation, chances are an attacker who can read the environment will be able to extract the secret from your application anyway. But if you deploy different applications to the same VM (or multiple application instances for different tenants), then I don’t trust the process isolation offered by containerization solutions to keep one container’s environment variables from a determined attacker with access to another container on the same machine.

If you pass the name (or, more technically speaking, the identifier) of a set of configuration properties, then you avoid the mentioned issues. The only precondition is that you must be free to re-organize these sets of properties anytime as you see fit.

It is true that this introduces a dependency on a service that somehow can resolve such configuration set identifiers; but that’s not much different from a dependency on, say, a database service that must be accessible for your application to start. And as long as this configuration service has a well defined API, you can easily mock it if necessary.

Spring Services

Back to the project I mentioned in the beginning: It uses a set of Spring Boot services in front of a document database. These services are packaged into Docker images that are deployed into a small cluster. (So far, Docker Swarm mode worked well for us. But if offerings like Azure’s managed Kubernetes service (AKS) make life simpler for us, I won’t rule out a switch to Kubernetes somewhere down the road.)

The Spring framework introduces the concept of an environment abstraction with profiles and property sources. Spring Boot builds on this environment abstraction and, out of the box, offers many options how you can pass configuration properties to your applications: “Traditional” property files, YAML configuration files, JVM system properties, command line arguments, OS environment variables, and so forth. In the end, all applicable property sources (according to the active profiles) are organized in a list managed by the environment abstraction. When the application needs the value of a specific property, Spring iterates over this list and uses the value from the first source that defines the property in question. Due to the order of the property sources in the list, more specific sources can override “default” configurations. If a property value references some other property, then the lookup begins again at the head of the list. Of course, it is possible to add custom property sources to the environment.

The Spring Boot configuration concept mostly worked well for us - we could define reasonable default configurations, configuration properties that go hand in hand (e.g., all TLS settings if we activate secure connections) can easily be grouped in a profile-specific configuration, and we could easily define additional profiles for new deployment targets. We only missed two crucial features: The configuration files should not be embedded into the docker images and secrets like database user credentials or private keys must not be kept in the configuration files.

Spring Cloud Config

From the recording of a SpringDeveloper presentation by Dave Syer and Josh Long I recalled that Spring Cloud Config addresses at least the former concern.

Config Server

The server part of Spring Cloud Config is a “normal” Spring Boot Web application that serves a list of property sources in a simple JSON structure. This is best shown by way of an example:

The following JSON object is the response of a local config server to a GET request to the URL http://localhost:9400/demo/plain-actuator-access,integration-db. The first URL path segment specifies the application name - a config server instance can serve the configuration of multiple applications. The second path segment specifies a comma-separated list of application profiles. Config Server also supports a third path segment (not used here) with a label that can be used, e.g., to request a particular version of the configuration.

{

"name": "demo",

"profiles": [

"plain-actuator-access,integration-db"

],

"label": null,

"version": null,

"state": null,

"propertySources": [

{

"name": "file:///Users/ludwigc/Java/JUG/authenticated-config-server/vault-config-client-demo/configurations/demo-integration-db.yml",

"source": {

"demo.db.host": "integrationtest.demo.contenthub.haufe.io"

}

},

{

"name": "file:///Users/ludwigc/Java/JUG/authenticated-config-server/vault-config-client-demo/configurations/demo-plain-actuator-access.yml",

"source": {

"management.security.enabled": false

}

},

{

"name": "file:///Users/ludwigc/Java/JUG/authenticated-config-server/vault-config-client-demo/configurations/demo.yml",

"source": {

"demo.db.host": "localhost",

"demo.db.database": "demo",

"demo.db.url": "jdbc:postgresql://${demo.db.host}/${demo.db.database}",

"demo.db.user": "${vault.demo.db.user}",

"demo.db.password": "${vault.demo.db.passord}",

"management.security.enabled": true

}

},

{

"name": "file:///Users/ludwigc/Java/JUG/authenticated-config-server/vault-config-client-demo/configurations/application.yml",

"source": {

"endpoints.shutdown.enabled": true

}

}

]

}

The important part of the response is the array propertySources: Each object in this array represents a property source that would be loaded in this order into the Spring environment if the demo application was started with the specified profiles and the corresponding config files in its classpath.

Note that the same property can be defined in multiple sources where the order of the property sources determines the “winner”. Furthermore, Spring resolves placeholders (using the ${...} syntax) recursively. Given only this property sources list, the property demo.db.url therefore resolves to jdbc:postgresql://integrationtest.demo.contenthub.haufe.io/demo.

Since this particular config service instance was run from within my IDE and I wanted it to serve configurations that reflected the content my local workspace, I started the config server with the native profile - with this profile, the server treats the configured file system folder as a read-only configuration source.

Unless the server is used for local development, it is more typical to make the server pull the configuration from a Git repository, though. More precisely, the config server is pointed to a local Git repository or configured to clone a remote repository on startup. When a client requests a configuration, the server fetches all relevant updates from the remote repository and checks out the branch or version specified as label in the client’s request. (If label is omitted from the URL, the config server defaults to the HEAD of the master branch.) Only then does the config server read the configuration files.

Sidenote: Config Server relies on Eclipse’s JGit library for all Git functionality. Unfortunately, JGit supports ssh-rsa keys only and does not understand hashed entries in the known_hosts file. This can easily lead to errors if there is already a hashed entry for the remote Git host. Since the error messages in the exceptions thrown by JGit are not clear at all, this issue is hard to diagnose - it cost me several hours when I gave config server my first tries.

If in doubt, you can check with ssh-keygen -F bitbucket.org whether your known_hosts file contains a key for, say, bitbucket.org. If for any of the returned keys the very first field does not show the relevant hostname in plain text, then you need to delete the keys from the known_hosts file and add a non-hashed ssh-rsa key instead:

$ ssh-keygen -R bitbucket.org

$ ssh-keyscan -t rsa bitbucket.org >> ~/.ssh/known_hosts

Config Client

The Spring Cloud Config client library fetches the relevant configuration properties from a config server and inserts them as property sources into your applications environment. All other configuration options are still supported, the environment will simply have additional sources. For your application code, it does not make any difference where the properties come from.

Of course, the config client also needs configuration - at the very least, it requires the address of a config server. Here Spring Boot’s bootstrapping phase enters the picture: Before a Spring Boot application starts to build its application context (where all the injection and autowiring of the application’s Spring beans takes place), it creates a bootstrapping context with all the components that are later used to build the application context. Among others, the bootstrapping context determines how the application context’s environment is set up.

The bootstrapping context’s environment uses the same sources available to every Spring boot application; the only difference is that the configuration files are called bootstrap.yml and bootstrap-profilename.yml (or bootstrap.properties and bootstrap-profilename.properties if you prefer to work with traditional property files).

As mentioned above, the config server can switch between branches in the underlying repository. The property spring.cloud.config.label controls the version or branch requested by the client application. We added the gradle-git-properties plugin to our project’s Gradle build whence the branch the application was built from is “known” at runtime as property git.branch. By setting spring.cloud.config.label=${git.branch} in bootstrap.yml, we make the application fetch the configuration from the branch that matches the source branch. This comes extremely handy if you want to test a feature branch that added or changed configuration properties.

So looking back to the twelve-factor app’s configuration approach, we can have some default configuration client properties (suitable, e.g., for local development) in our application’s bootstrap.yml and override, say, the config server endpoint at deployment time using an environment variable. The config server address is not sensitive and there will only be very few properties that vary between deployments whence the environment variable approach is well manageable.

As part of an application’s health check, the config client also periodically reloads the configuration from the server. Most of the time, the environment is read only during the application context initialization, so the reload won’t have much effect - unless you annotate your beans with @RefreshScope. This seems a nice feature for on-the-fly changes, but I don’t have first-hands experience with it yet.

Hashicorp Vault

With Spring Cloud Config, we serve configurations that are stored inside a Git repository - in our case, inside the actual code repository. By now it should be common knowledge that you should not store plain secrets in your Git repositories - at the very least, the secrets must be properly encrypted with a key stored separately from the repository. (Few years ago, some developers learned it the hard way when they got charged by Amazon for resources unauthorized users could consume because the AWS credentials were found in public repositories.)

Few developers are experts in cryptography, so getting encryption right is hard. And you don’t want to maintain lots of additional code that intercepts your configuration properties and decrypts them before they are used by your application. In the end, you are better off with a dedicated secret store solution like Hashicorp Vault.

Hashicorp Vault is a tool for secure access to secrets that takes care of the secrets’ encryption at rest, can record any secret access in an audit log, and comes with an elaborate access control concept. It also supports dynamic secrets like db passwords created on-the-fly that will automatically be deleted again once the corresponding Vault token expires. All interaction with a Vault instance takes place via its (typically TLS-secured) REST interface.

One of the features we are using on top of the generic secret store is Vault’s PKI backend that can issue X.509 certificates; it essentially offers a private CA. (The CA’s registration authority is de facto realized by Vault’s roles and access control implementation.) For endpoints accessed by customers and partners (including other projects within Haufe), we of course configure TLS certificates issued by one of the “well-known” CAs; thanks to Let’s Encrypt, it nowadays is no hassle anymore to obtain a certificate that your clients are likely to trust. But within our application, we need to secure some internal communication paths by TLS with client authentication. Let’s Encrypt does not issue client certificates, so a private CA accessible via Vault’s REST interface makes operation much simpler.

Spring Cloud Vault

Similar to Spring Cloud Config, a Spring Cloud Vault client inserts additional property sources into an Spring Boot application’s environment. The properties are secrets stored in Vault, though.

You can even have profile-specific secrets: Vault stores the secrets as JSON objects; You address these JSON objects by a hierarchical path name similar to a filesystem path, starting with the mount name of the respective secret plugin.

haufe-lexware-blog-chludwig ludwigc$ vault read -format=json local-secrets/ch-integrationtests/CHinteg

{

"request_id": "0ca07792-c7da-625b-0dd7-57b794fb9856",

"lease_id": "",

"lease_duration": 604800,

"renewable": false,

"data": {

"vault.content.apiKey": "*********",

"vault.content.clientId": "*********",

"vault.content.clientSecret": "*********",

"vault.ingest.apiKey": "*********",

"vault.ingest.clientId": "*********",

"vault.ingest.clientSecret": "*********"

},

"warnings": null

}

Above you see the response I get from a local Vault instance (with the actual secret values asterisked by me) when I query the object at the path local-secrets/ch-integrationtests/CHinteg. The actual secrets are stored inside the data object. Given a Spring Boot application ch-integrationtests in profile CHinteg, the Spring Cloud Vault client will fetch the secrets from the Vault locations local-secrets/ch-integrationtests/CHinteg, local-secrets/ch-integrationtests, local-secrets/defaultContext/CHinteg, and local-secrets/defaultContext. The defaultContext is a name specified in your application’s bootstrap.yml; it is meant to hold secrets shared by multiple applications.

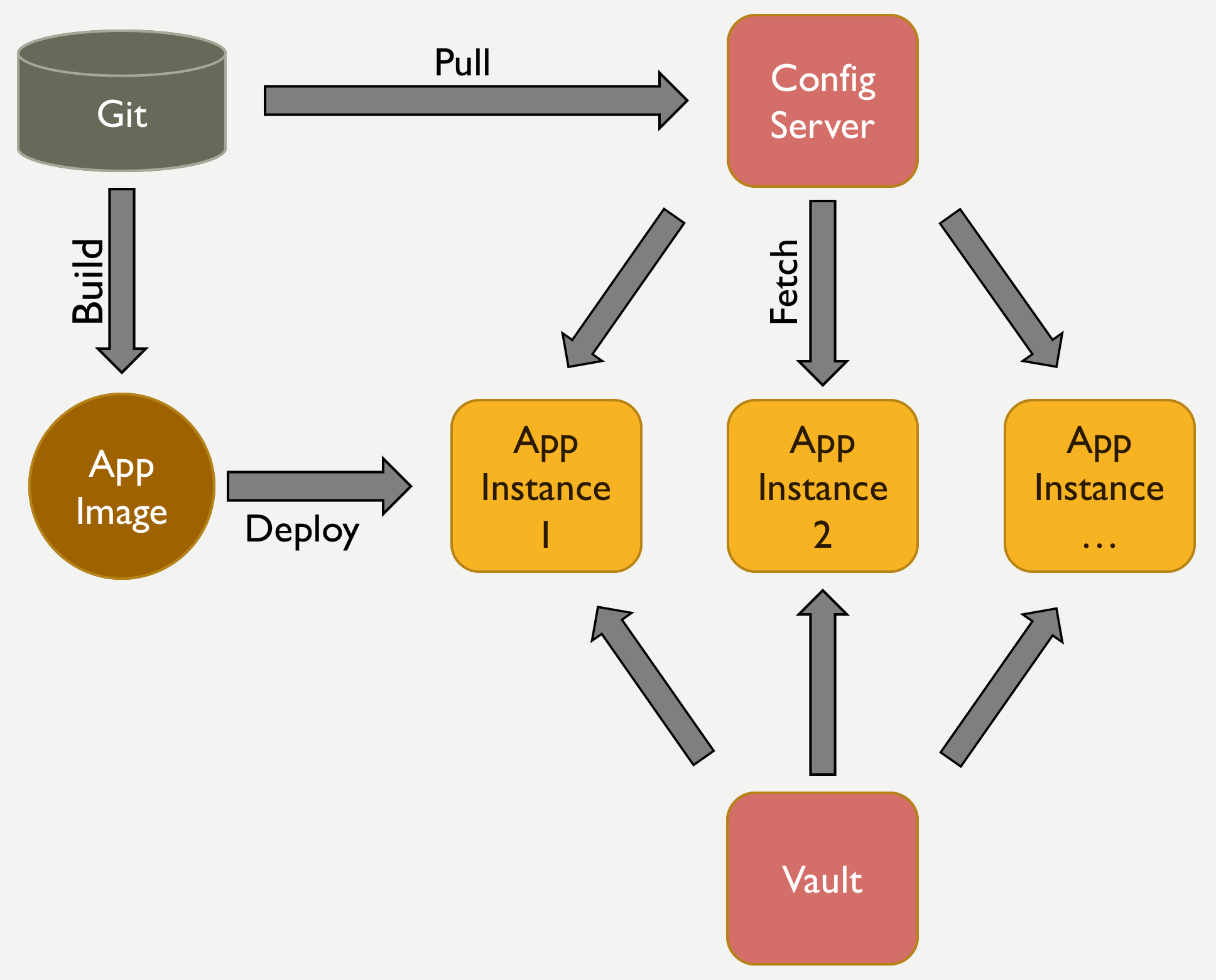

The following diagram shows the data flow if you activate both Spring Cloud Config and Vault in your application:

Vault Authentication

Spring Cloud Vault supports the Vault authentication methods that are relevant for authentication by a service; among others, AppRole and Token authentication are supported. The Spring Cloud Vault client also takes care of token renewal. But how can we pass in the necessary credentials to our application instances? After all, the Vault credentials are at least as valuable as the most sensitive secret accessible in Vault.

Within the project, we have two types of applications:

-

Batch jobs that run, say, once a day and that are started as a single instance only, respectively. Here Vault’s one-time secret-ids for use with AppRole authentication are a perfect match: The deployment pipeline requests a new secret-id from vault that expires after its first use. This secret-id is passed in to the application by, say, an environment variable. The application will immediately exchange this secret-id for a Vault token - afterwards, the secret-id is useless. Therefore, a potential attacker has a very small time window only to steal and use the secret-id.

Even if an attacker succeeds, this will not go unnoticed: The application’s login attempt will fail if an attacker used the secret-id. This must be logged as a security incident whence an immediate response is possible.

-

Long-running services that are deployed into a Docker Swarm cluster. Some of the services are replicated whence multiple application instances need to login to Vault after a deployment - a one-time secret-id won’t be sufficient. An

n-time secret-id (wherenis the number of service instances) won’t cut it either because the cluster is free to restart a service instance at any time in order to, say, move the instance to another worker node. We therefore must pass a secret-id to the service instances that must not get into the hands of an attacker.Fortunately, Docker Swarm Mode makes it possible to share secrets with service instances. (Kubernetes has a similar feature.) First, the deployment pipeline asks Vault for a new secret-id and stores it as a secret in the cluster. Docker sends the secret to the cluster manager over a mutually authenticated TLS connection and encrypts the secret at rest in the cluster’s Raft store:

$ vault write -f –format=json auth/approle/role/myapprole/secret-id |\ jq -r '.secret_id' |\ docker secret create myapprole_secretid -Second, the deployment pipeline requests the swarm to start our service and to make the secret created above available to the service instances. The secret will be mapped into the service instances’ container file system, but this mount stays in memory only:

$ docker service create --name="myapp" \ --secret="myapprole_secretid" myapp:alpineNote that the value of the secret-id never appears in a command line or environment variable.

Spring Cloud Vault Extensions at Haufe

In our use of Spring Cloud Config and Vault we encountered additional requirements that were not met out of the box. Fortunately, they offer sufficient hooks for customization.

Authorized Config Server

We split our configuration properties: Sensitive properties are stored in Vault, the rest is managed in our Git repository and served to the application instances via Spring Config Server. The config server does therefore not expose secrets.

Nevertheless, a config server provides more insight into the internal structure of an application than we want to hand out freely to potential attackers. This is not an attempt of “security by obscurity”, but unnecessary information exposure (CWE-200) can still aid attackers in their attacks. If a config server is accessible via the internet or for most of the company over the intranet, then we’d like to require some client authentication.

HTTP Basic Authentication over TLS should be sufficient for this purpose (assuming a strong enough password). This is also very easy to realize - all we had to do was add Spring Security to the Spring Config Server. A Spring Cloud Vault client in the config server obtains the credentials from Vault, whence the Spring Security configuration can set up an in-memory user store - that’s run-of-the-mill Spring Boot service development.

On the client side, the situation was more tricky: Service instances that use such a secured config server need access to the credentials as part of their config client bootstrap setup. The credentials are secrets and are kept in Vault. However, the properties fetched by Spring Cloud Vault are visible in the “regular” application context’s environment only, they are not available in the bootstrap environment yet!

I perused the documentation and stepped through the Spring Boot application initialization code with a debugger. I had hoped that I could tell Spring Boot (e.g., by adding an @Order annotation) to load the secrets from Vault first and only then start to initialize the Spring Cloud Config client - to no avail. Whatever I tried, the Config Client never saw the properties read by the Vault client.

When I went over the Spring Cloud Config documentation again, I finally had an idea: The Spring Cloud Config client supports service discovery. Spring Cloud ships with implementations for, e.g., Eureka or Consul, and in its typical use case the client will learn the config server’s address by discovery. But as with most Spring features, it is easy to supply a custom implementation of the discovery client; and the discovery client interface supports basic authentication credentials. The following shows the core of the discovery client implementation stripped of documentation, logging, and most error handling:

public class VaultBasedDiscoveryClient implements DiscoveryClient {

public static final String CONFIG_SERVICE_ID = "configserver";

public static final String URI_PROPERTY_NAME = "spring.cloud.config.uri";

public static final String USERNAME_PROPERTY_NAME = "spring.cloud.config.username";

public static final String PASSWORD_PROPERTY_NAME = "spring.cloud.config.password";

public static final String CONFIG_PATH_PROPERTY_NAME = "spring.cloud.config.configPath";

private final ConfigClientProperties configClientProperties;

private final PropertySourceLocator vaultPropertySourceLocator;

private final Environment environment;

private final Supplier<List<ServiceInstance>> memoizedConfigServiceListSupplier;

public VaultBasedDiscoveryClient(ConfigClientProperties configClientProperties,

PropertySourceLocator vaultPropertySourceLocator,

Environment environment) {

this.configClientProperties = configClientProperties;

this.vaultPropertySourceLocator = vaultPropertySourceLocator;

this.environment = environment;

}

@Override

public String description() {

return "Vault-based Discovery Client";

}

@Override

@Deprecated

public ServiceInstance getLocalServiceInstance() {

return null;

}

@Override

public List<ServiceInstance> getInstances(String serviceId) {

VaultBasedConfigServiceInstance serviceInstance = null;

if (CONFIG_SERVICE_ID.equals(serviceId)) {

serviceInstance = createServiceInstance();

}

return serviceInstance != null ?

Collections.singletonList(serviceInstance) :

Collections.emptyList();

}

@Override

public List<String> getServices() {

return Collections.singletonList(CONFIG_SERVICE_ID);

}

private VaultBasedConfigServiceInstance createServiceInstance() {

PropertySource<?> vaultPropertySource =

vaultPropertySourceLocator.locate(environment);

URI uri = getUri(vaultPropertySource);

if (uri == null) {

return null;

}

String userInfo = uri.getUserInfo();

String username = getUsername(vaultPropertySource, userInfo);

String password = getPassword(vaultPropertySource, userInfo);

String configPath =

getVaultProperty(CONFIG_PATH_PROPERTY_NAME, vaultPropertySource, null);

return new VaultBasedConfigServiceInstance(CONFIG_SERVICE_ID, uri,

username, password, configPath);

}

private URI getUri(PropertySource<?> vaultPropertySource) {

String uriString =

getVaultProperty(URI_PROPERTY_NAME, vaultPropertySource,

configClientProperties.getUri());

try {

return StringUtils.isNotBlank(uriString) ? new URI(uriString) : null;

}

catch (URISyntaxException e) {

return null;

}

}

private String getUsername(PropertySource<?> vaultPropertySource, String userInfo) {

String defaultUsername = configClientProperties.getUsername();

if (userInfo != null) {

String[] userInfoParts = userInfo.split(":", 2);

defaultUsername = userInfoParts[0];

}

return getVaultProperty(USERNAME_PROPERTY_NAME, vaultPropertySource,

defaultUsername);

}

private String getPassword(PropertySource<?> vaultPropertySource, String userInfo) {

String defaultPassphrase = configClientProperties.getPassword();

if (userInfo != null) {

String[] userInfoParts = userInfo.split(":", 2);

if (userInfoParts.length > 1) {

defaultPassphrase = userInfoParts[1];

}

}

return getVaultProperty(PASSWORD_PROPERTY_NAME, vaultPropertySource,

defaultPassphrase);

}

private String getVaultProperty(String propertyName,

PropertySource<?> vaultPropertySource,

String defaultValue) {

Object property = vaultPropertySource.getProperty(propertyName);

if (property != null) {

return property.toString();

}

return defaultValue;

}

}

If VaultBasedDiscoveryClient#getInstances(String serviceId) is called with the service id "configserver", then it delegates the request to VaultBasedDiscoveryClient#createServiceInstance() that, in turn, reads the required properties from a PropertySource provided by a VaultPropertySourceLocator. The latter class is part of Spring Cloud Vault and makes the properties retrieved from Vault accessible.

Username and Password are also looked up in an instance of ConfigClientProperties, the type-safe configuration class of the Spring Cloud Config client. This way we can still use the “standard” configuration of the config client as a fall-back if a property is not specified in Vault.

You might have noticed the lack of any Spring annotation on VaultBasedDiscoveryClient - it is not a @Component or similar. Creation of an VaultBasedDiscoveryClient instance as a Spring bean is rather the task of the configuration class VaultBasedDiscoveryClientAutoConfiguration:

@Configuration

@ConditionalOnExpression("${haufe.cloud.config.vaultDiscovery.enabled:true} and ${spring.cloud.vault.enabled:true}")

@ConditionalOnMissingBean(VaultBasedDiscoveryClient.class)

@AutoConfigureAfter(RefreshAutoConfiguration.class)

@Import(VaultBootstrapConfiguration.class)

public class VaultBasedDiscoveryClientAutoConfiguration {

@Resource(name = "vaultPropertySourceLocator")

private PropertySourceLocator vaultPropertySourceLocator;

@Bean

DiscoveryClient discoveryClient(@Autowired ConfigClientProperties configClientProperties,

@Autowired Environment environment) {

return new VaultBasedDiscoveryClient(configClientProperties,

vaultPropertySourceLocator, environment);

}

}

This class is an example of the parts of Spring Boot I am not so keen of: For me, at least, such an amassment of annotations always makes it hard to understand their net effect.

Anyway, let’s give it a go:

@Configurationdeclares this class as a contributor of Spring beans to the application context, subject to the conditions in the following annotations.- The annotation

@ConditionalOnExpressionrequires that both propertieshaufe.cloud.config.vaultDiscovery.enabledandspring.cloud.vault.enabledmust betrue, otherwise this configuration class will be ignored. - Thanks to the

@ConditionalOnMissingBeanannotation, this configuration class will only be used if there was noVaultBasedDiscoveryClientbean instantiated by other means yet. @AutoConfigureAfter(RefreshAutoConfiguration.class)tells Spring this configuration should only be applied once Spring’s logging setup etc. is complete.@Import(VaultBootstrapConfiguration.class)loads the bean definitions from Spring Cloud Vault’s auto-configuration - in particular, the bean namedvaultPropertySourceLocator.

With the VaultBasedDiscoveryClientAutoConfiguration on the classpath (and enabled), the config client will refer to a VaultBasedDiscoveryClient for its own configuration and load the required properties - including the config server credentials - from Vault.

PKI Key- & Truststore Integration

The management of TLS key material is an often irksome task. Tools like openssl or Java’s keytool are not very intuitive to use and few developers are familiar with all options. Unfortunately, the fact that your application still works as expected does not imply your security is sufficiently strong. It therefore is even more important that we automate the handling of TLS keys and trust stores to avoid undetected mistakes due to manual operations.

In many cases, you can take advantage of services like Let’s Encrypt that - in a fully automated fashion - issue certificates trusted by most clients. But you still need to make the key material available in a secure way to your applications. If your services are not publicly available, then you are sometimes best off to use certificates issued by a private certificate authority. In particular, this is often the case if you rely on mutually authenticated TLS to secure connections between your services.

Traditionally, we used to place a key (and / or trust) store file with the necessary key material into the file system where the application could load them from. It is certainly possible to store such key stores as generic secrets in vault and download them before the application starts - say, as part of a Docker entrypoint script - into a folder inside a Docker tmpfs mount. This takes care of the distribution of the keys and certificates to the application instances, but you’d still need to prepare key stores before you can upload them into vault.

Mark Paluch demonstrated in his sample code how to make a Spring Boot application’s embedded web server load the TLS keys directly from vault (i.e., without touching the file system). If you use Vault’s PKI backend as a private CA, then the services will even request new certificates on-the-fly.

In fact, the sample code focuses on the latter part. But it caches issued certificates in a generic secret store and loads them from there if possible. This can easily be adapted to scenarios where we upload keys and certificates obtained from external CAs to vault.

We extended the service code to load trust stores as well from vault. A trust store admittedly does not need to be secret; nevertheless, you must guarantee the trust store’s integrity or an attacker might be able to make your application accept a certificate issued by or for the attacker. Furthermore, we added the ability to configure a TLS client.

Trustore Configuration From Vault

The CertificateBundles implemented as part of Spring Vault include a Base64 string representation of the private key, the certificate, the issuer’s certificate, as well as the certificate’s serial number. Mark Paluch’s sample code includes a EmbeddedServletContainerCustomizer that makes the embedded Web container use the content of a CertificateBundleread from Vault for TLS server authentication. Unfortunately, it always injects a truststore that contains the issuer certificate of the server certificate only. Since it is very common that CAs issue either server certificates or client certificates (but not both), this truststore setting did not meet our requirements.

We therefore decided to load the trusted certificates from Vault as well. The class TrustedCertificates of our extension is quite simple - it contains lists of truststore entries that, in turn, consist of the Base64 string representation of a certificate plus a certificate alias used by Java to refer to the certificate. The method readTrustedCertificates(VaultOperations, String) we added to CertificateUtils reads such a TrustedCertificates object from Vault. All the “heavy lifting” is taken care of by VaultOperations#read(String, Class<T>) implemented by Spring Vault.

TrustedCertificates#createTrustStore() builds an in-memory Java KeyStore from these entries. For user convenience, the implementation strips PEM certificate begin and end markers and removes all whitespace from the certificate representation. This makes it possible to store the certificates in Vault in either PEM or Base64-encoded DER format.

With these extensions in place, we could modify the implementation of the EmbeddedServletContainerCustomizer in VaultPkiConfiguration such that it either injects a truststore obtained from Vault or - if no such truststore was configured - a copy of the JVM’s default truststore.

TLS Client Configuration From Vault

So far, we discussed the configuration of the embedded servlet container of a Spring Boot application. Often, your application also acts as an HTTP client of backend services and the client also needs a custom TLS configuration - maybe the service uses a certificate from a private CA that the JVM does not trust by default or your client has to authenticate itself using an X.509 client certificate.

The Spring @Configuration class ServiceClientTLSConfig creates a TLSClientKeyMaterial Spring bean that bundles private key material (i.e., keystore, keystore password, and key password) as well as trust material (i.e., truststore and truststore password). If both spring.cloud.vault.enabled and haufe.client.ssl.vault.enabled are true and if there is a VaultOperations bean available in the Spring context (i.e., Spring Vault is avilable and actived), then TLSClientKeyMaterial will be initialized with values read from a Vault generic secret backend. The data format for storing the key material in Vault is the same as for the server key material.

In some cases (like local development against an integration instance of the backend service), it might still be more convenient to use key- and truststores on the file system, though. ServiceClientTLSConfig accommodates such a scenario; simply set haufe.client.ssl.vault.enabled to false, then the TLSClientKeyMaterial will be initialized from the filesystem. This is controlled by Spring Boot’s @ConditionalOnXYZ annotations on the bean creation methods: ServiceClientTLSConfig#tlsClientKeyMaterialFromVault(ServiceClientTLSProperties, VaultOperations) will be called only if all the conditions mentioned above are met. In all other cases, ServiceClientTLSConfig#tlsClientKeyMaterialFromFilesystem(ServiceClientTLSProperties) loads key material from the file system. (At first glance, the use of @ConditionalOnXYZ might seem like overkill; however, it avoids unsatisfied Spring bean dependencies if we want to run the application with Vault support turned off because then there won’t be a VaultOperations bean.)

How you make your HTTP client use the key material depends on your HTTP client implementation, of course. The demo repository contains an example in the module demo-service-frontend: The component ClientHttpRequestFactoryConfigurer uses the TLCLientKeyMaterial bean injected into the constructor by Spring to set up an SSLContext that, in turn, is used to construct a HttpComponentsClientHttpRequestFactory. I expect that the setup for other client implementations would look similar.