What is this about?

This was a proof-of-concept project to find out what it takes to access on-premise data (in the form of our Lexware pro product line) from an internet client, even though that data resides behind company firewalls, without forcing our customers to open an incoming port to the outside world. This would be a different approach than, say, “Lexware mobile”, which synchronizes data into the cloud, from where it is accessed by client devices.

There was a fair amount of work already done in the past, which made the job easier. For a couple of years now, Lexware pro installs a service in the LAN, running on the same computer on which the database server resides. This service opens a port and accepts HTTP requests originating from the local network. These REST requests, depending on the url, are relayed to various business services. Again we profit from work which began many years ago, to encapsulate business logic in modules which can run in their own processes (separate from the actual Lexware pro application) and with their own database connections.

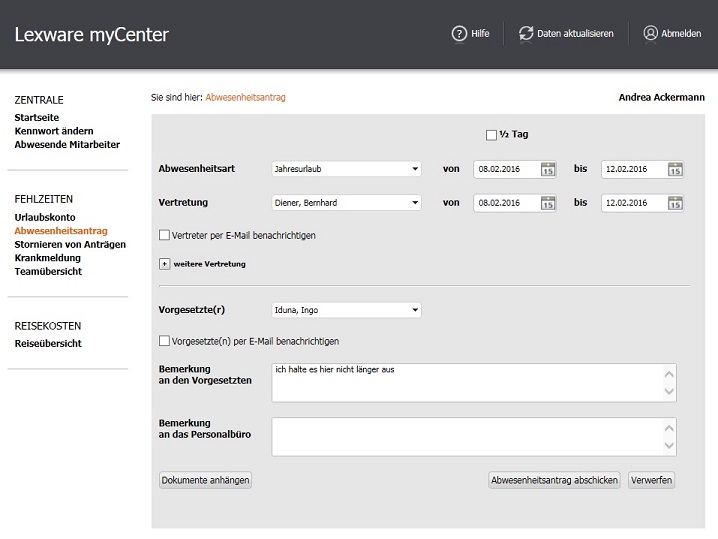

These HTTP REST Api’s are currently used by “Lexware myCenter”.

Okay, what is Lexware myCenter?

Typically, Lexware pro is installed in the HR department of our customer’s company. This means that the other employees of this company have no access to the application. However, there are plenty of use-cases which would make some kind of communication attractive, for example:

- The entire workflow for applying for vacation (that’s “holiday” for you Brits)

- Employee applies for vacation from his boss

- Boss approves (or not) and relays the application to HR

- HR approves (or not) and informs the employee

- The entire workflow for employee business trips

- Similar approval workflow to above

- In addition, employee gathers travel receipts which must be entered into the system

Previously, these workflows took place “outside the system”. Everything was organized via e-mail, paper (yes, Virginia, paper exists), telephone, and face-to-face, until it was ready for HR to enter into the system.

With myCenter, every employee (and her boss) may be given a browser link and can carry out her part of the workflow independently. The necessary data is automatically transfered from/to the on-premise server via the HTTP REST Api. Of course, it only works within the company LAN.

Enter Azure Service Bus Relay

Azure Service Bus Relay allows an on-premise service to open a WCF interface to servers running in the internet. Anyone who knows the correct url (and passes any security tests you may implement) has a proxy to the interface which can be called directly. Note that this does not relay HTTP requests, but uses the WCF protocol via TCP to call the methods directly. This works behind any company firewall. Depending on how restrictive the firewall is configured, the IT department may need to specifically allow outgoing access to the given Azure port.

So we have two options to access our business services on the desktop.

- Call our business service interfaces (which just happen to be WCF!) directly and completely ignore the HTTP REST Api.

- Publish a new “generic” WCF interface which consists of a single method, which simply accepts a “url”-argument as a string and hands this over the HTTP REST Api, then relays the response back to the caller.

Both options work. The second option works with a “stupid” internet server which simply packs the url of any request it gets from its clients into a string and calls the “generic” WCF method. The first option works with a “smart” internet server (which may have advantages), this server having enough information to translate the REST calls it gets from its clients into business requests on the “real” WCF interfaces.

For the Reisekosten-App, we decided on the first method. Using a “smart” internet server, we could hand-craft the Api to fit the task at hand and we could easily implement valid mock responses on the server, so that the front-end developer could get started immediately.

However, the other method also works well. I have used it during a test to make the complete myCenter web-site available over the internet.

Putting it all together

With the tools thus available, we started on the proof-of-concept and decided to implement the use-case “Business traveller wants to record her travel receipts”. So while underway, she can enter the basic trip data (dates, from/to) and for that trip enter any number of receipts (taxi, hotel, etc.). All of this information should find its way in real-time into the on-premise database where it can be processed by the HR department.

Steps along the way

The on-premise service must have a unique ID

This requirement comes from the fact that the on-premise service must open a unique endpoint for the Azure Service Bus Relay. Since every Lexware pro database comes with a unique GUID (and this GUID will move with the system if it gets reinstalled on different hardware), we decided to use this ID as the unique connection ID.

The travelling employee must be a “user” of the Lexware pro application

The Lexware pro application has the concept of users, each of whom has certain rights to use the application. Since the employee will be accessing the database, she must exist as a user in the system. She must have very limited rights, allowing access only to her own person and given the single permission to edit trip data. Because myCenter has similar requirements, the ability for HR to automatically add specific employees as new users, each having only this limited access, was already implemented. So, for example, the employee “Andrea Ackermann” has her own login and password to the system. This, however, is not the identity with which she will log in to the App. The App login has its own requirements regarding:

- Global uniqueness of user name

- Strength of password

- The possibility to use, for example, a Facebook identity instead of username/password

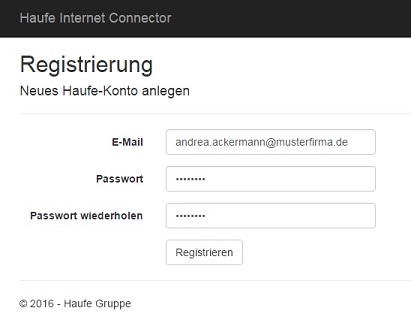

The user must do a one-time registration and bind the App identity to the unique on-premise ID and to the Lexware pro user identity

We developed a small web-site for this one-time registration. The App user specifies her own e-mail as user name and can decided on her own password (with password strength regulations enforced). Once registered, she makes the connection to her company’s on-premise service:

Here is the registration of a new App user:

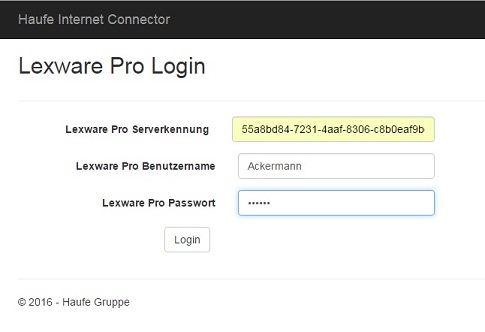

And, once registered and logged in, the specification of details for the Lexware pro connection:

The three values are given to the employee by her HR manager

Lexware pro Serverkennung: The unique on-premise service ID

Lexware pro Benutzername: The employee’s user name in the Lexware pro application

Lexware pro Passwort: This user’s password in the Lexware pro application

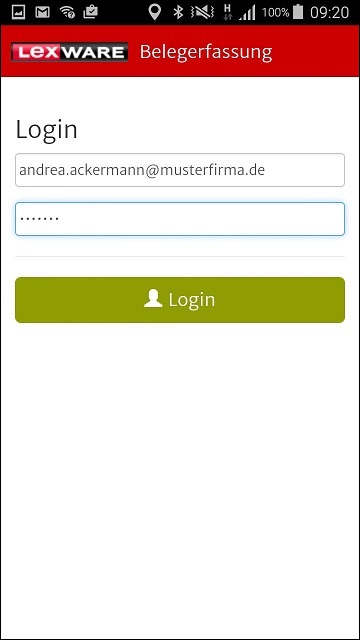

The connection and the Lexware pro login are immediately tested, so the password does not need to be persisted. As mentioned, this is a one-time process, so the employee never needs to return to this site. From this point on, she can log in to the smartphone App using her new credentials:

The Reisekosten-App server looks up the corresponding ‘Lexware pro Serverkennung’ in its database and connects to the on-premise Relay connection with that path. From that point on, the user is connected to the on-premise service of her company and logged in there as the proper Lexware pro user. Note that the App login does not need to be repeated on that smartphone device, because the login token can be saved in the device’s local storage.

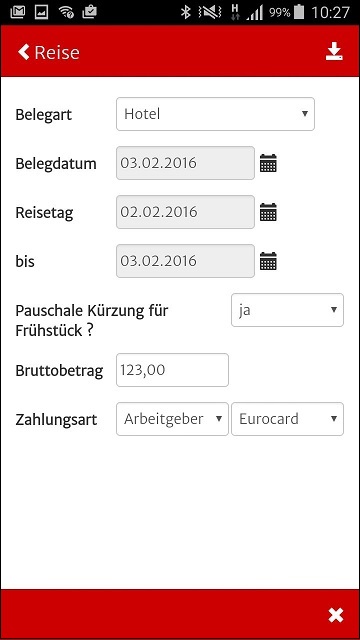

And here is a screenshot of one of the views, entering actual receipt data:

Developing the Front-End

The front-end development (HTML5, AngularJS, Apache Cordova) was done by our Romanian colleague Carol, who is going to write a follow-up blog about that experience.

What about making a Real Product?

This proof-of-concept goes a long way towards showing how we can connect to on-premise data, but it is not yet a “real product”. Some aspects which need further investigation and which I will be looking into next:

- How can we use a Haufe SSO (or other authentication sources) as the identity?

- How do we register customers so that we can monetize (or track) the use?

- Is the system secure along the entire path from the device through Azure and on to the on-premise service?