Introduction

Both Holger and I have been writing quite some about our Open Source API Management System wicked.haufe.io (GitHub Repository), and today we want to announce the new release 0.10.0 of wicked, which was published yesterday.

We have been quite busy with various things, mostly concerning

- Support for the OAuth 2.0 Implicit Grant and Resource Owner Password Grant

- Upgrading to the latest Kong version (as of writing 0.9.4)

- Stability and Diagnostic Improvements

- Integration testing Kong

- Displaying Version information

- API Lifecycle Support (deprecating and unsubscribing by Admin)

I would like to tell you some more about the things we did, in the order of the list above.

OAuth 2.0 Implicit Grant and Resource Owner Password Grant

In the previous versions, wicked was focussing on machine-to-machine type communication, where both parties (API consumer and API provider) are both capable of keeping secrets (i.e., in most cases server side implementations). As I was writing in my post introducing wicked.haufe.io, the next logical step would be to ease up not only the Client Credentials (M2M) OAuth 2.0 flow, but also additional flows which are needed in modern SPA and Mobile App development:

- Implicit Grant Flow

- Resource Owner Password Grant Flow

What do we want to achieve by using these flows?

The main problem with SPAs (Single Page Applications) and Mobile Apps is that they are not capable of keeping secrets. Using an approach like the Client Credentials flow would require e.g. the SPA to keep both Client ID and Client Secret inside its JavaScript code (remember: SPAs are often pure client side implementations, they don’t have a session with their server). All code, as it’s in the hands of either the Browser (SPA) or Mobile Device (Mobile App) have to be considered as public.

What we want to achieve is a way to let the SPA (or Mobile App) get an Access Token without the need to keep Username and Password of the end user in its storage, so that, using the Access Token, the API can be accessed on behalf of this user:

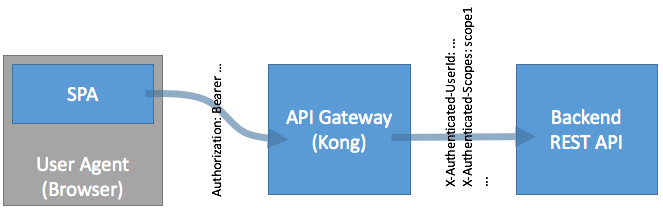

The SPA only has an access token, which (a) is an opaque string, and (b) does not contain any manipulatable content, so that the API Gateway can inject the desired information into additional headers based on this access token (here: X-Authenticated-Userid and X-Authenticated-Scope). The Backend REST API then can be 100% sure the data which comes via the API Gateway is reliable: We know the end user, and we know what he is allowed to, because it’s tied to the Access Token.

How does the Implicit Grant work?

The way of the Implicit Grant to push an Access Token to an SPA works as follows, always assuming the end user has a user agent (i.e. a Browser or component which behaves like one, being able to follow redirects and get POSTed to):

- The SPA realizes it needs an Access Token to access the API (e.g. because the current one returns a

4xx, or because it does not have one yet) - The end user is redirected away from the SPA onto an Authorization server, or is made to click a link to the Authorization Server (depending on your UI)

- The Authorization Server checks the identity (authenticates) the end user (by whatever means it wants),

- The Authorization Server checks whether the authenticated end user is allowed to access the API, and with which scopes (this is the Authorization Step)

- An access token tied to the end user’s identity (authenticated user ID) and scopes is created

- … and passed back to the SPA using a last redirect, giving the

access_tokenin the fragment of the redirect URI

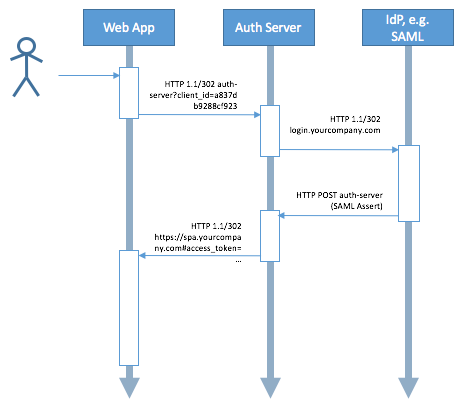

Applied to e.g. an Authorization Server which relies on a SAML IdP, the simplified version of a swim lane diagram could look as follows:

How does the Resource Owner Password Grant work?

In contrast to the Implicit Grant Flow, where the user does not have to enter his username and password into the actual SPA/Mobile App, the Resource Owner Password Grant requires you to do just that: The user authenticates using his username and password, and these are exchanged for an access token and refresh token which can subsequently be used instead of the actual credentials. The username and password should actually be thrown away explicitly after they have been used for authenticating. This flow is intended for use with trusted Mobile Applications, not with Web SPAs.

The flow goes like this, and does not require any user agent (Browser):

- The Mobile App realizes it does not have a valid Access Token

- A UI prompting the user for username and password to the service is displayed

- The Mobile App passes on username, password and its client ID to the Authorization Server

- The Authorization Server authenticates the user (by whatever means it wants), and authorizes the user (or rejects the user)

- Access token and refresh token are created and passed back to the Mobile App

- The Access Token is stored in a volatile memory, whereas the Refresh Token should be stored as safely as possible in the Mobile App

- The API can now be accessed on behalf of the end user, using the Access Token (and the user credentials can be discarded from memory)

In case the Access Token has expired, the Refresh Token can be used to refresh the Access Token.

wicked and Authorization Servers

Now, how does this tie in with wicked? Creating an Authorization Server which knows how to authenticate and authorize a user is something you still have to implement, as this has to be part of your business logic (licensing, who is allowed to do what), but wicked now has an SDK which makes it a lot easier to implement such an Authorization Server. There is also a sample implementation for a simple Authorization Server which just authenticates with Google and deems that enough to be authorized to use the API: wicked.auth-google. In addition to that, there is also a SAML SDK in case you want to do SAML SSO federation with wicked (which we have successfully done for one of our projects in house): wicked-saml.

After having implemented an Authorization Server, this component simply has to be deployed alongside the other wicked components, as - via the wicked SDK - the authorization server needs to talk to both wicked’s backend API and the kong adapter service, which does the heavy lifting in talking to the API Gateway (Mashape Kong).

In case you want to implement an Authorization Server using other technology than the proposed node.js, you are free to just use the API which the Kong Adapter implements:

Details of the API can be found in the wicked SDK documentation. Especially the functions oauth2AuthorizeImplicit, oauth2GetAccessTokenPasswordGrant and oauth2RefreshAccessToken are the interesting ones there.

Upgrading to latest Kong (0.9.4)

Not only wicked has evolved and gained features during the last months, but also the actual core of the system, Mashape Kong has been released in newer versions since. We have done quite some testing using the newer versions, and found out some changes had to be done to make migration from older versions (previously, wicked used Kong 0.8.3).

In short: We have migrated to Kong 0.9.4, and you should be able to just upgrade your existing wicked deployment to all latest versions of the wicked components, including wicked.kong, which just adds dockerize to the official kong:0.9.4 docker image.

In addition to upgrading the Kong version, we have now also an integration test suite in place which at each checkin checks that Kong’s functionality still works as we expect it. Running this integration test suite (based on docker) gives us a good certainty that an upgrade from one Kong version to the next will not break wicked’s functionality. And if it does (as was the case when migrating from 0.8.x to 0.9.x), we will notice ;-)

Stability and Diagnostics

As mentioned above, we have put some focus on integration testing the components with the actual official docker images, using integration tests “from the outside”, i.e. using black box testing via APIs. Currently, there are test suites for the portal-api (quite extensive), the portal and the portal-kong-adapter. These tests run at every checkin to both the master and next branches of wicked, so that we always know if we accidentally broke something.

We know, this is standard development practice. We just wanted you to know we actually do these things, too.

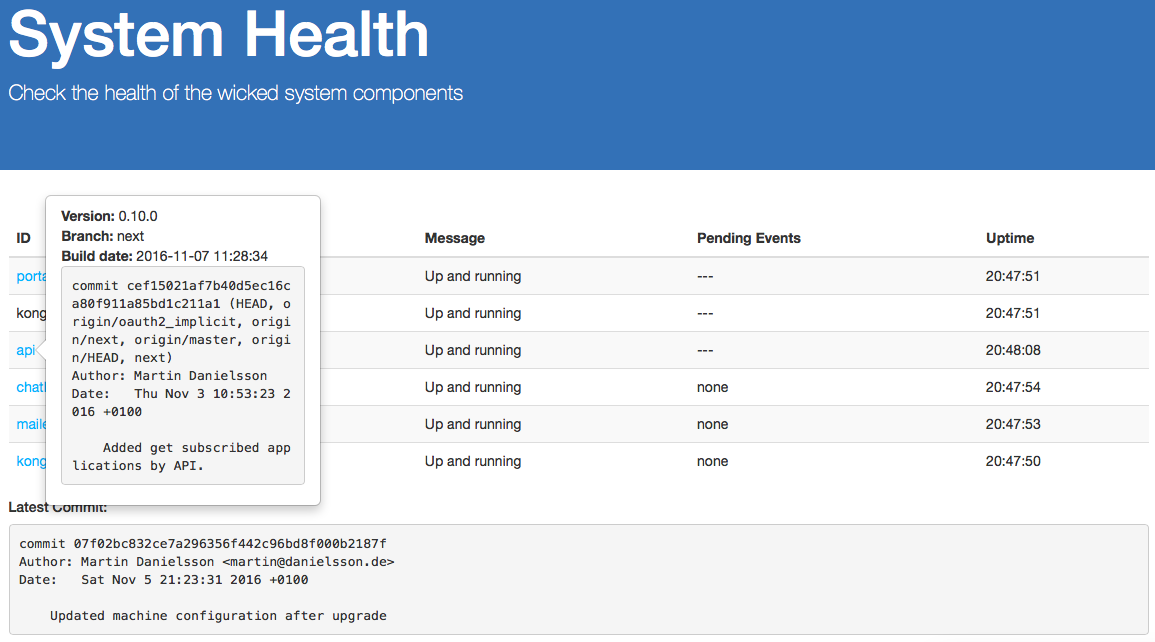

If you have a running portal instance, you will now also be able to see which version of which component is currently running in your portal deployment:

API Lifecycle Support

By request of one of the adopters of wicked, we introduced some simple API lifecycle functionality, which we think eases up some of the more tricky topics and running an API:

- How do you phase out the use of an API?

- How can you make sure an API does not have any subscriptions anymore?

- How can you contact the consumers of an API?

To achieve this, we implemented the following functionality:

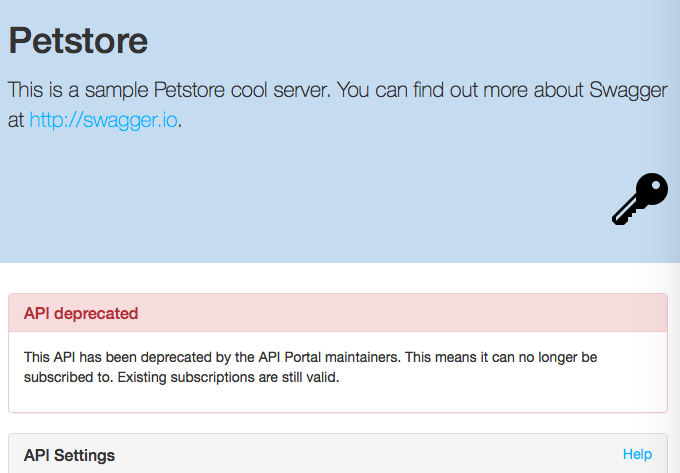

- It is now possible to deprecate an API; developers will not be able to create new subscriptions to that API, but existing subscriptions are still valid

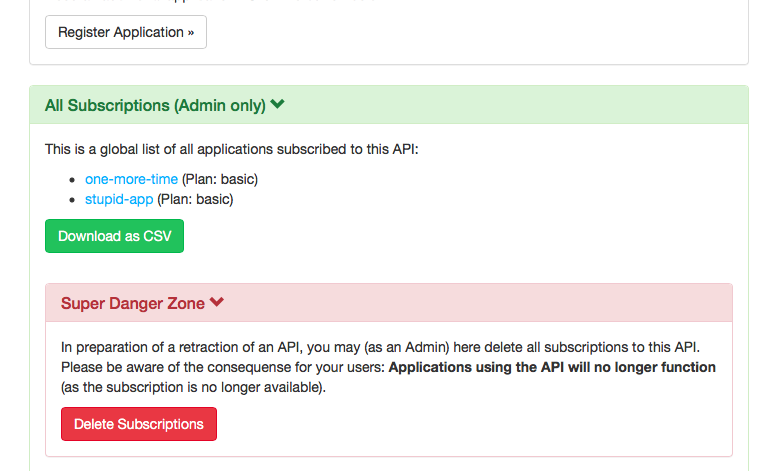

- You can now - as an administrator - see the list of subscribed applications on the API Page

- It’s also possible to download a CSV file with all subscribed applications, and the owner’s email addresses, e.g. for use with mass mailing systems (or just Outlook)

- Finally, you can delete all subscriptions to a deprecated API, to be able to safely remove it from your API Portal configuration (trying to delete an API definition which still has existing subscriptions in the database will end up with

portal-apinot starting due to the sanity check failing at startup)

A deprecated API in the API Portal

CSV Download and Subscription Deletion

What’s next?

Right now, we have reached a point where we think that most features we need on a daily basis to make up a “drop in” API Management Solution for Haufe-Lexware have been implemented. We know how to do OAuth 2.0 with all kinds of Identity Providers (including our own “Atlantic” SAML IdP and ADFS), and we can do both machine-to-machine and end-user facing APIs. If you watched carefully, we do not yet have yet explicit support for the OAuth 2.0 Authorization Code Grant, so this might be one point we’d add in the near future. It’s (for us) not that pressing, as we don’t have that many APIs containing end user resources we want to share with actual third party developers (like Google, Twitter or Facebook and such), but rather APIs which required authorization, but we (as Haufe-Lexware) are the actual resource owners.

The next focus points will rather go in the direction of making running wicked in production simpler and more flexible, e.g. by exploring docker swarm and its service layer. But that will be the topic of a future blog post.

Man, why do I always write so long posts? If you made it here and you liked or disliked what you read, please leave a short comment below and tell me why. Thanks!